Vaccinating teachers is crucial for returning to school

This blog was first published on March 15, 2021, on the Global Partnership for Education website.

As countries roll out plans to inoculate their populations against COVID-19, the urgent need to vaccinate teachers is an increasingly pressing concern. But are teachers prioritized in national plans? Here’s an overview of what some countries are currently doing for teachers, and recommendations on why teachers must be considered as a priority group.

As countries proceed with rollout plans to inoculate their populations against COVID-19, the urgent need to vaccinate teachers is an increasingly pressing concern. The pandemic crippled education systems across the world.

By April 2020, most of the world’s schools were closed. To expedite their reopening, countries must act to protect teachers’ health, safety and wellbeing. This is a critical precursor to the renormalization of in-person teaching and learning and to the much-needed return of the socialization function of education.

In December 2020, UNESCO and Education International (EI), the global federation of education unions, issued a call to governments and the international community to consider the vital importance of vaccinating teachers and school personnel.

As UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay and EI’s General Secretary David Edwards say in their joint video message,

Reopening schools and education institutions safely and keeping them open as long as possible is an imperative. In this context, as we see positive developments regarding vaccination, we believe that teachers and education support personnel must be considered as a priority group.”

As early as March 2020, the Teacher Task Force had launched an international Call for Action on Teachers to highlight critical measures that countries should take regarding teachers in the global pandemic, including the “protection of teachers’ and students’ health, safety and well-being”.

This was reaffirmed during the Extraordinary session of the Global Education Meeting (2020 GEM), convened by UNESCO in October 2020, where heads of state and ministers committed to support all teachers and education personnel as frontline workers and to prioritize their health and safety.

What countries are vaccinating teachers?

The Teacher Task Force notes that despite the urgency of protecting teachers and other education personnel, and the international community’s attempts to promote their priority for vaccination, they are not consistently prioritized in national plans, which is partly due to a slow global rollout.

Where well-defined rollout plans exist, most countries tend to give priority to health care workers, the elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions putting them at high risk.

One exception is the jurisdiction of New Delhi in India, where all personnel, including teachers, who were actively involved in the city’s COVID-19 management efforts will be vaccinated on a priority basis as front line workers.

Chile has been relatively successful in its program to vaccinate teachers. To prepare for the return to classes, the Chilean government included teachers and education workers early on in the country’s massive vaccination drive. In just the previous two weeks, more than half of the country’s 513,000 teachers and education workers received shots in time for the start of the school year.

Credit: UNICEF/ Raphael Puget/UNI342143

Teachers in the second wave

In other countries, teachers are included in the second priority group for vaccination. This is true in Argentina, Colombia and Turkey. In Vietnam, teachers are given higher priority as they will be vaccinated in the same group as senior citizens and people with chronic illnesses, along with other workers providing essential services and diplomats.

Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, teachers are listed in the second priority group along with first responders, the military, those working in the justice system, transport workers and public servants essential to the pandemic response. Some who question this ranking have launched an online petition to Parliament to prioritize teachers and school/child care staff.

In a three-phase plan, teachers in South Africa are listed in a very large second-level priority group comprising around 17 million people, which includes essential workers such as police officers, persons in congregate settings such as prisons and shelters, people aged 60 and over, and people with various comorbidities.

Some countries have indirectly given precedence to teachers by taking the approach of prioritizing workers writ large, in order to spur stalled economies. In Indonesia, teachers along with the elderly form a second priority group in the national rollout plan. The country aims to vaccinate 5 million teachers by June.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, it was announced in early February that all primary teachers would be vaccinated, and by the end of the month teachers under the age of 40 registered on the health directorate’s list could sign up online to receive the vaccine.

With an increasing global rollout, some major commitments have been made. In the United States, all states have been asked to give priority to teachers in vaccination efforts, in accordance with a goal to have all pre-primary to secondary teachers and child care workers receiving their first shots by the end of March.

Similarly, the Ministry of Education in Singapore announced that it would begin vaccinating 150,000 teachers and other staff in educational institutions from as of early March.

Little information is available from African countries. Rwanda, however, which received 347,000 doses of vaccine from the UN-backed COVAX initiative in early March, has emphasized the vaccination of teachers, with the Ministry of Health stating that “teachers and lecturers are among the frontline workers being vaccinated against COVID-19.”

Elsewhere on the continent, teachers in Uganda will be included in the second priority group after health care workers and security personnel, while Kenya has also put teachers in a high priority group, after health care workers and security personnel but before those with possible comorbidities and over 58 years old.

Teachers still missing out

In other countries such as Italy and Brazil, teachers are relegated to a lower position in national plans for vaccine prioritization. Brazil has grouped teachers with security workers and prison staff, which has led to strikes in Sao Paulo to protest, among other issues, the health concerns that teachers face in schools.

In the Russian Federation, a certain mistrust of the vaccine may hamper efforts to vaccinate teachers, despite their high priority along with medical staff and social workers, in initial stages of mass vaccination.

Recently, new statistics reveal that two-thirds of poorer countries will face education budget cuts. This is problematic for numerous reasons, two of the main ones being the need to vaccinate teachers and recruit staff to meet the challenges of increased workload, teacher attrition and illness.

Many low-income countries are unlikely to obtain enough doses to vaccinate their teachers for some time. This puts massive pressure on teachers to teach in-person while unvaccinated putting theirs and others’ health at risk.

A recent study suggests that without greater international cooperation, more than 85 poor countries will not have widespread access to coronavirus vaccines before 2023.

Recommendations

In view of the global situation outlined above, the Teacher Task Force makes the following recommendations:

-

As called for by UNESCO and Education International, teachers should be considered frontline workers and a high-priority group to be vaccinated early to ensure that schools can reopen safely for in-person education.

-

Governments should work with teacher unions to ensure that all schools continue to adhere strictly to rules of safe operation, and that unvaccinated teachers have access to psychological and socio-emotional care, sick leave and support from school leaders and district/central level authorities.

-

Where high-priority groups require identification for access to vaccination, ministries should ensure that teacher lists are accurate and that teachers have adequate identification.

-

Lessons learned from previous pandemics should inform vaccine distribution plans to ensure that dissemination mechanisms are effectively put in place and run efficiently so that all teachers have access, including those in remote regions.

-

Governments should ensure adequate funds are available to support vaccination roll out to guarantee the safety of teachers and education support staff and the safe reopening of schools.

***

Cover photo credit: Bret Bostock/Flickr

Caption: A medical syringe with a vaccine

Shadow Education in Africa - Private Supplementary Tutoring and its Policy Implications

A reflection on teachers’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Where do we go from here?

This blog has been written by Lisa E. Kim & Kathryn Asbury from the Department of Education, University of York, UK.

As schools around the world continue to adapt to and move on from COVID-19 we consider how teachers can best be supported.

The content of this blog is based a series of interviews we conducted with 24 primary and secondary teachers in England as part of a longitudinal research project “Being a teacher in England during the COVID-19 pandemic” funded by the Economic and Social Research Council.

Several of the teachers in our study used this analogy to describe their experience of an initial shock, and of being thrown into disarray, when the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly and unforeseeably affected their lives as teachers.

In England, teachers have worked through partial school closures in March 2020, re-openings for some year groups by mid-June 2020, full re-openings in September 2020, partial closures in January 2021, and are now preparing for possible phased re-openings in March 2021. We share some reflections on the stories teachers have told us about their experiences of being a teacher during the pandemic.

Teachers are overloaded and exhausted

Working under increased demands and with limited resources during the pandemic has taken a toll on the teachers in our study. One secondary teacher said to us in November:

Part of this overload seemed to be associated with not knowing what lies ahead and how to prepare students for an uncertain future, including the handling of high-stakes national assessments.

Moreover, many teachers reported being physically and emotionally exhausted, which are well-known symptoms of burnout. Burnout is a consequence of prolonged experience of stress, and can have negative consequences for teachers, students, and educational systems, such as greater intention to quit the profession and poorer student outcomes. It is noteworthy that school leaders have reported more anxiety during 2020 than class teachers, which raises particular concern for this group and for the potential effects on leadership it could have.

Teachers are concerned for their pupils

The teaching profession is inherently a social one, involving interacting with pupils and their families. However, the pandemic has caused communication barriers, especially with some pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds who may have limited access to technology and broadband. As one primary teacher described:

“...some of those families, they're just incredibly hard to get hold of”.

Teachers told us that this lack of access to some pupils, especially those known to be vulnerable in some way, caused them significant concern for their pupils’ learning and wellbeing.

That said, teachers have shown themselves to be resilient and adaptive. To ensure pupils’ immediate learning and nutrition needs are addressed, some teachers reported delivering work packs, laptops, and food packs, where financially and logistically possible. They also told us that they called pupils and their families regularly, and created new communication channels through which they were most likely to engage with families, such as Facebook. As one primary school leader said: “As teachers we want to connect and we want to be there for the kids that we teach. And we want to keep those relationships going even when that's really tricky.”

Policy and practice recommendations

A recurring theme that emerged from the interviews was a need for clear direction on how to move forward. In light of all that has occurred in the last year, policy-makers, schools, and teachers are called to work together to collaboratively pave a path forward from the COVID-19 experience. These recommendations are in line with the Teacher Task Force’s Call for Action to support teachers.

- Government and the teaching community will both benefit from collaborative dialogues

With a pressing need to respond rapidly to the ever-changing pandemic, governments have had to make difficult decisions quickly. However, participants told us that teachers have often felt excluded from contributing to decisions that directly affect them, making them feel less valued as a profession than before the pandemic. Creating channels whereby representative members of the teaching community can contribute to decision-making processes will be beneficial both for policy-makers — ensuring plans are practically feasible on the ground — and teachers — ensuring that their views are considered in decisions that affect them.

- Schools and parents will benefit from working together

The importance of working together with families has been particularly highlighted in this pandemic. As one secondary school leader put it: “It's got to be... a partnership where you're in communication with parents on a regular basis. The parents know what you're trying to do, [but] they know their kids better than you do, and they can support you in trying to get the best for the children”. In the early months of the pandemic, we saw evidence of increased effort and success in establishing and strengthening school–parent relationships, and a feeling among teachers that parents appreciated them, even when they felt that the wider society didn’t. Schools and parents can benefit from sustaining this relationship to achieve the common goal of healthy development and wellbeing for their pupils and children.

- Teachers must support one another

Social support is an important job resource that can buffer the effects of job demands, and providing this for one another can be beneficial. Teachers told us that it has been difficult not being able to meet each other, such as through corridor conversations and lunchtime breaks in staff rooms. In light of this, some teachers seemed to be finding alternative ways to connect with colleagues, such as via departmental virtual platforms and social media channels. Finding and using adaptive ways to receive social support, while still protecting work–life boundaries, is likely to help teachers manage stress.

- The general public needs to recognise teachers’ contributions

In England, teachers are classed as critical workers and have worked throughout the pandemic. However, a common media portrayal of teachers has been that they are lazy and not working. Images and beliefs such as this must be corrected, as there is evidence that they can negatively affect teachers’ quality of instruction. As a society we must fully appreciate teachers, as they continue work to support the learning and welfare of pupils in their country during the pandemic.

Teachers are foundational to our educational systems and it is vital that we listen to their experiences and support them as we move forward.

Here are some extra resources for policy-makers and school leaders supporting hybrid learning and the return to school:

- Supporting teachers in back-to-school efforts - Guidance for policy-makers - Teacher Task Force, UNESCO, ILO, 2020

- Supporting teachers in back-to-school efforts – A toolkit for school leaders - Teacher Task Force, UNESCO, ILO, 2020

- Education responses to COVID-19: an implementation strategy toolkit, OECD, 2020

- Building back better: education systems for resilience, equity and quality in the age of COVID-19, World Bank, 2020

NB.: The content of this blog does not reflect the views of the University of York or the ESRC but only that of the authors. Most project findings are currently published as preprints and may therefore change during the peer review process.

The authors thank the participants who generously shared their stories with them and the research assistants (Suzanna Dundas, Diana Fields, Rowena Leary, and Laura Oxley) for their contributions to the project.

Photo credit: Annie Spratt/Unsplash

Organization Constraints on Professional Development: An Exploration into How Institutional Frameworks Hold Back Teacher Training

Roles of Teachers in the SDG4 Age: An Introductory Note

Teachers as Tutors: Evidence from Africa

This blog was written by Mark Bray, UNESCO Chair Professor in Comparative Education at the University of Hong Kong, and Director of the Centre for International Research in Supplementary Tutoring (CIRIST) at East China Normal University (ECNU). It reflects the author's opinions, which are not necessarily those of the TTF.

Shadow education and implications for policy

The theme of non-state actors in education, which has huge importance throughout the world, will be the focus for the 2021 edition of UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report. A key dimension includes the private supplementary tutoring undertaken by public school teachers. In the literature, private supplementary tutoring is commonly called shadow education. The metaphor is used because as the curriculum changes in schools, so it changes in the shadow; and as the school system expands, so does the shadow.

Shadow education has long been visible in East Asia, and is now a global phenomenon. While shadow education has received much attention in Egypt and some other parts of North Africa, it is neglected in Sub-Saharan Africa. This article draws on a book entitled Shadow Education in Africa (available in English and in French), the genesis of which was a background paper for UNESCO’s GEM Report.

How widespread is shadow education?

Reliable statistics are scarce, and one message of the book is that better data are urgently needed. Nevertheless, the following statistics shed some light on the prevalence of shadow education.

- In Angola 94% of surveyed students in Grades 11 and 12 (2015) were receiving or had received tutoring at some time.

- In Burkina Faso, 46% of surveyed upper primary students (2014/15) were receiving tutoring at the time of the study.

- In Egypt, 91% of Grade 12 respondents (2014) indicated that they were either currently receiving tutoring or, if they had graduated, had done so before completion.

Other sources show trends over time (Table 1), with significant growth that has likely continued. Some of this tutoring is provided by commercial entrepreneurs who operate tutorial centres, and some is provided by university students and others who operate informally. In Africa, most tutoring is provided by in-service teachers taking additional employment as part-time occupations.

Table 1: Enrolment Rates in Private Tutoring, Grade 6, 2007 and 2013 (%)

Source: SACMEQ National Reports.

What issues arise when teachers are also tutors?

Private supplementary tutoring can be beneficial. It can help slow learners to catch up with their peers, and can strengthen countries’ overall human capital. It also provides extra income for teachers, perhaps helping to retain them in the profession. In many African countries, high proportions of school personnel are contract teachers who commonly have relatively low salaries. Even teachers forming part of the civil service may feel that their salaries are inadequate to meet all family needs.

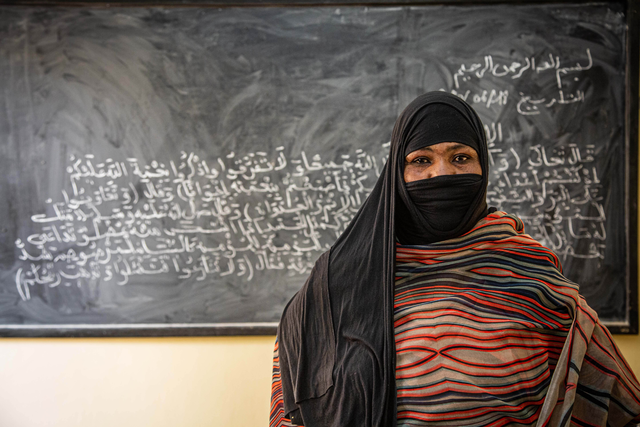

Source: http://gem-report-2017.unesco.org/en/countonme

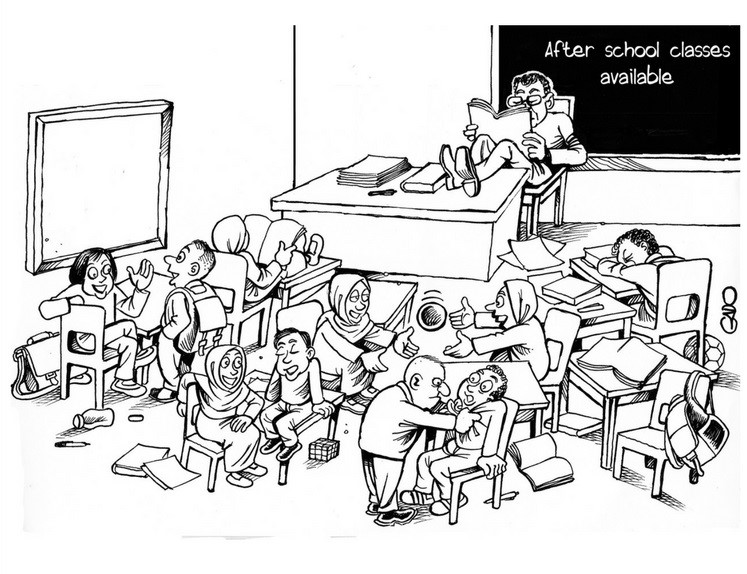

Yet when teachers are also tutors, several problematic issues arise. One is that the teachers may neglect their regular teaching duties in order to devote time and energy to their private lessons. Especially problematic situations arise when teachers tutor the students for whom they are already responsible in mainstream schooling. For example, the danger arises of deliberate reduction of attention during regular lessons in order to promote demand for private tutoring. Dangers also arise of discrimination in the classroom, when teachers openly or covertly favour the students receiving supplementary lessons from them.

What are the policy implications?

The first need is for the topic to be taken out of the shadows – to be discussed not only by Ministry of Education personnel but also by professional bodies at sub-national, school and community levels. Some governments, e.g. in Egypt, Eritrea, The Gambia and Kenya, explicitly prohibit private tutoring by serving teachers. Other governments, for example in Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, permit such tutoring but prohibit it on school premises. Another category, exemplified by Mozambique, permits private tutoring with official permission but explicitly forbids teachers from tutoring their existing students.

Yet many of these policies exist more on paper than in practice. Governments do not have strong machinery to enforce prohibitions, especially when many actors are sympathetic to the status quo. Thus, even parents may exert pressures on teachers and schools since they want their children to perform well in a competitive environment. Parents frequently feel their children’s teachers know the children best and can therefore provide better support than tutorial centres or other providers.

This situation underlines the need to accompany policies with practical measures to ensure better regulation. Yet sometimes governments feel that the mechanisms to monitor and regulate the practice are inadequate, leading to the development of laissez-faire policies that do little to regulate the problem.

What about the school level?

Even if governments turn a blind eye to the problem, schools can issue their own policies and monitor patterns to avoid ethical malpractice. Schools can help explain the issues to parents, and support finding alternatives to support their children’s needs. School-level policies may be especially effective, since teachers and parents are well known to one another resulting in that guidelines and sanctions are more likely to be meaningful and effective. Nevertheless, it must be recognised that sometimes schools are complicit in encouraging tutoring in order to generate extra revenue for institutional and/or personal uses.

Learning from each other

Some people assume that if the quality of schooling is improved, then shadow education will disappear by itself. Global trends however show the opposite. The East Asian countries that have much shadow education also have strong education systems. Rather, globalisation has increased pressures on families to compete resulting in that shadow education is on the rise in many European and high-income countries. Thus also in Denmark and Finland, which are renowned for the quality of their schooling, the expansion of shadow education is visible. This trend suggests that shadow education is a concern not only in countries where it is already strong but also in those where it is not so strong. In the latter case, policy-makers have the opportunity to shape the sector before it becomes engrained in cultures..

Further, the fact that large-scale shadow education has been evident for a longer time in Asia, may bring insights for other parts of the world. One regional study on this theme is entitled Regulating private tutoring for public good.

This is how we're supporting teachers around the world in 2021

This International Day of Education, celebrated on Sunday 24 January, will recognise the inspiring collaborations around the world that have safeguarded education in times of crisis. To mark the occasion we are highlighting initiatives, partnerships and best practices to support teachers and learners.

We asked Teacher Task Force members to share their plans for 2021, a year in which it will be critical to join forces and combine resources to recover from the pandemic and move forward together in support of teachers.

At least a third of the world’s students have not been able to access remote learning during Covid-19 school closures. Students in low and lower-middle income countries lost an average of about four months of schooling, compared to six weeks in high-income countries. Recovering from this situation will present an unprecedented challenge.

However, school closures have also made people appreciate the importance of schools and the key role of teachers – not only for academic and economic reasons, but also for learners’ socio-emotional development. Covid has been a wake-up call to ensure education systems become more resilient, inclusive, flexible and sustainable. It has also shown the capacity of systems and teachers to innovate to ensure teaching and learning can continue despite challenging circumstances.

Out-of-the-box thinking

Teacher Task Force members have been sharing how initiatives demonstrated by teachers during 2020 school closures have inspired plans for 2021.

VVOB – education for development will focus in 2021 on managing further disruptions to education, remediating learning losses due to these disruptions, and building the socio-emotional wellbeing of youth. It will promote blended capacity development trajectories for teachers and school leaders that can help include those left behind, building on experiences in countries including Rwanda.

GPE’s response to the pandemic included support to distribute portable radio sets in Sierra Leone and launch of a regular educational broadcast within one week of school closures. In 2021, GPE will continue to fund training and management information systems, working with partner countries to identify challenges and find solutions.

Using radio to reach rural schools in Chile, TV in Nigeria and an enhanced online platform in Malaysia are among 50 stories in reports published by Teach For All’s global network on how teacher leadership, distance learning and the efforts of communities have helped keep children learning through the pandemic. In 2021, the network will continue its Learning Through the Crisis initiative to support the reopening of schools and creation of more resilient, sustainable education systems.

The Education Commission and the Education Development Trust, in partnership with WISE, are working with governments to fully understand the roles of school leaders and their support for teachers during school closures and reopenings of the past year. The research will be translated into a policy playbook highlighting important lessons learned and insights from several countries.

Technology for professional development

The pandemic not only shifted learning online for many students, it opened up new possibilities in using technology for teachers’ professional development. STiR Education used virtual meetings and radio to reach teachers in India and Uganda, and in 2021, they aim to embed technology more deeply into their work while ensuring that their activities are equitable for all teachers.

The Commonwealth of Learning will in 2021 develop tailored professional development courses in partnership with the UK’s Open University. It will offer courses on mobile learning and cybersecurity for teachers, as well as help teachers in various Commonwealth countries improve their skills in developing subject-specific digital resources.

The Inter-American Teacher Education Network, an initiative of the Organization of American States, creates teams of educational leaders who have worked on projects such as virtual professional development in Argentina, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay. Applications for 2021 project teams are open until February 1.

Global School Leaders created Upya, a curriculum to enable school leaders in marginalized communities to lead effectively through this pandemic.

OEI will continue its work to strengthen the capacities of teachers in the Ibero-American region, with a broad focus in 2021 on digital skills. There will be projects aimed at improving STEAM methodology, offer digital resources, and new scholarships in order to contribute to increase the doctoral formation in the region.

ProFuturo will keep offering online free training courses for teachers worldwide, while Enabel will continue teacher training in Burundi including use of information and communication technologies and rolling out online and hybrid courses in Uganda.

Meanwhile, the Center for Learning in Practice at the Carey Institute for Global Good is working virtually with stakeholders, including teachers, to co-develop teacher professional learning materials. As a result, they will provide quality holistic on-line learning in displacement contexts across the Middle East, East Africa, and Central/West Africa.

Whilst digital will be central to future education systems, hands-on face-to-face learning will still be important. The LEGO Foundation will continue to support partners in Bangladesh, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and Vietnam who are providing play-based teacher professional development that will reach up to 65,000 teachers in 2021.

Supporting education systems in every setting

Many Teacher Task Force members work with governments to support strengthening and managing system efficiencies and the overall performance of the sector.

In Burkina Faso, UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) is supporting the government to improve its human resources management and related budgeting in education. IIEP, together with the Education Development Trust, is exploring the role of “instructional leaders”, who support teachers to develop their skills without a formal role in assessment and will publish research in 2021 including case studies from Wales, India, Shanghai, Jordan, Rwanda and Kenya.

The Institute’s first ever Hackathon in January 2021 will include addressing challenges to improve the deployment of teachers, reducing disparities between a country’s regions, and identifying ghost teachers – who can cost up to 20% of the education budget in some countries. Lastly, IIEP plans to publish research in 2021 on teacher management in refugee settings in Jordan and Kenya.

Priorities for Education International in 2021 include calling for teachers and education staff to be considered a priority group in global vaccination efforts, and promoting a Global Framework of Professional Teaching Standards developed with UNESCO.

Building on the fact that the best-performing countries in the pandemic were those that engaged in meaningful dialogue with education unions, Education International calls for the dialogue to continue on issues such as the use of technology in education, investment in the workforce, professional development, decent working conditions, and respect for teachers’ professional autonomy.

Working together for teachers

2020 was an unprecedented year across every sector. In education, it shone a light, not only on the systemic gaps and challenges witnessed across the world, but also on the mitigating responses developed organically by teachers. It also saw emergency measures developed and implemented by education stakeholders at different levels, governments and the international development community.

While 2020 accelerated innovation in education and the process to reimagine its future delivery, efforts in 2021 will build on this to reposition and strengthen teachers’ roles in building more resilient systems of education in a post-covid-19 context. The members of the Teacher Task Force aim to be a driving force in this work.

*

Photo caption: A math teacher in Cambodia. Credit: VVOB – education for development

Teachers at the centre of a revitalised education system

In the lead up to International Day for Education, the Teacher Task Force spoke to Michelle Codrington-Rogers, who is a secondary school citizenship teacher in Oxford, and the President of the United Kingdom NASUWT (National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers).

In a few days’ time it will be International Day for Education, and the United Nations will be calling to strengthen and revitalize education systems, and recognize teachers as frontline workers. How do you think governments can support teachers in 2021?

Teachers and educators have held together education systems for decades. And with the COVID-19 pandemic, the glue and sticky tape that teachers have been using to hold together education systems has become very evident. Which means that, after the pandemic, we need to be talking about giving teachers back the professional respect they deserve and recognising that we aren't glorified babysitters. Teachers are highly trained, highly qualified professionals. Governments need to help rebuild that trust with the profession. They need to empower us with the ability to make the decisions that impact on the students and young people that we have in front of us, and trust us to use our own professional judgement to provide the best education and life choices that we can for the next generation.

The kind of teacher leadership that you are talking about really became apparent during the pandemic. Can you give us some examples of teacher and school leadership that you saw thriving in 2020?

What was amazing during the pandemic was to see groups of teachers coming together, to pool resources and help each other through creating professional spaces to work together. There are many teachers out there who are thinking of new and innovative ways to engage young people and students. In the UK, the Oak Academy was a great example of this – it was made by teachers, for teachers, who came together and said, let’s share our resources. Another example is a group that formed on social media, allowed teachers from literally all over the world to come together and share ideas - for example how to use Bitmojis in your online learning spaces. What is interesting is that, on a daily basis, we don’t usually have the opportunity to share ideas even with our own colleagues within our school. The pandemic has given us that space again, where we can collaborate and inspire each other.

It also means that we can learn from each other – I honestly believe that the best schools and the best learning environments are where we are all learning from each other. The best teachers, the most inspirational ones, are those who are willing to acknowledge that we’ve always got more to learn.

One of the areas in which you and your colleagues have been showing leadership is your work in decolonising the curricula. Can you tell us about this work and the challenges you have faced?

I am first generation British and my family is originally from the Caribbean. So I grew up knowing my identity and my family’s background and history, but also conscious that my parents and my grandparents were taught British history. This is true for millions of people around the world – that they are being taught a version of history which doesn’t reflect them nor the experiences of peoples who were colonised at some stage of their past.

We've been campaigning in many different guises, with students, in schools, universities and in communities, to decolonise the curricula. The events of 2020 and the Black Lives Matter movement have helped show the importance of re-educating people, especially about how important it is to understand systemic discrimination and prejudice. And it’s not only about history, it’s about teaching how this history has led to where we are today, in the relationships and societies we have today, in a multicultural world and as global citizens. It also means that many teachers have also had to learn about this, as they themselves had been taught a much narrower version of history.

I'm so proud that Education international, during their last global world congress, passed a motion in support of this. Which means that we have teachers and educators from across the world, speaking about what that ‘decolonising’ means in their countries. It means that people from across the world, from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and parts of Africa are becoming visible in their own curricula and in the history being taught in their own countries.

This change has to happen at all levels – among educators and students and communities. In our case, it is very much the fruit of leadership taken by teachers and schools. But we also hope that eventually this will lead to systemic change at the national level, adopted by governments.

Recently you participated in a discussion on the Future of Teachers, organised by UNESCO’s Futures of Education initiative. What do you think will be the main challenges for the teaching profession in the next five years?

The challenges faced by teachers are going to be political, economic and social. From the political point of view, teachers are going to need to be at the heart of conversations – and even struggles – to define what is education about and what it is for. Teachers and teaching are at the centre of those discussions, as there is a tension between traditional and new digital ways of learning. As teachers, we are going to need to be part of helping re-define what this means. We can’t lose sight that teaching is a human interaction built on relationships, and that AI and digital learning can’t replace that.

From an economic point of view, we know that every country’s public purses have been hit by the pandemic. For example, in the UK teachers will not be receiving any pay increase, even after 10 years of austerity. In many countries, teachers are financially way behind where they should be as a profession – and they need to be able to at least pay their bills. So we are faced with a situation where teacher salaries are stagnant, but the stress and workload are increasing. There is a point where teaching as a profession is going to become less and less attractive and there will be less and less people willing to become teachers.

Lastly, teachers are going to be expected to help repair the connections and bonds which have been broken by lockdowns and school closures. Schools aren’t just an academic space; they are also a space in which children and young people are nurtured, and citizens are forged. But to do this teachers and educators are going to need professional respect and trust. What is positive, is seeing how many young people today are politically and socially aware, and conscious of their power and ability to change the world. We have the next generation of social activists who are going to make our world better if not for themselves, then definitely for their children and the next generations. So, I am hopeful - hopeful that education will be a space for us to move the world in that positive direction.

How the global school testing culture takes a heavy toll on teachers’ morale

This blog draws substantially from the recent open-access article School Testing Culture and Teacher Satisfaction by William C. Smith & Jessica Holloway, published in Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability.

In many parts of the world, teachers are held responsible for their students’ test scores. Why does this practice harm teacher morale to such an extent? New research suggests that the answer lies partly in the way test scores are used in teacher appraisals – and points to the dangers of this pervasive practice.

Teachers are subject to increased scrutiny and often the first to be blamed for educational shortcomings. Testing for accountability, where educators are held accountable for student test scores, has spread from the United States and the United Kingdom around the globe. In Portugal and Chile, for example, teachers’ salaries are linked to test scores.

Past research highlights that such practices are harmful to teacher satisfaction. High-stakes, test-based accountability has decreased teacher morale, as well as increased work-related pressure and personal stress. In the United Kingdom, for example, teachers in high-stakes environments have described their disappointment when they realize “the reality of teaching being worse than expected, and the nature (rather than the quantity) of the workload”.

How do such systems lead to teacher dissatisfaction? The way teacher appraisals are used and communicated can help explain the relationship. Teacher appraisals, and the feedback teachers receive from such evaluations, are an important part of that environment and can influence how teachers feel about themselves and their work. Nearly all teachers across 33 countries reported teaching in systems where student tests scores were used in their appraisals as part of a high stakes decision.

The increased use of high-stakes testing to hold teachers accountable reflects what some have called a global testing culture. In a testing culture, student test scores are understood to accurately represent student learning and teachers are expected to do everything in their power to improve test scores for their students and school. Those that fail to fall in line with such a culture can be stigmatized for not being a team player or blamed for not sufficiently preparing students for tests.

Data from 33 countries that participated in the OECD’s 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) sheds light on the direct and indirect influence of school testing culture on teacher satisfaction.

There is strong evidence that school testing cultures directly damage teacher satisfaction. They can also cause damage indirectly through the appraisals that teachers receive from principals. How test scores are emphasized in appraisals and the perceived utility of appraisal feedback can shape teachers’ responses to such feedback.

Working within a school testing culture appears to be the norm for most teachers: 97% work under a teacher appraisal system that is based, at least in part, on student test scores. The majority work for a principal who reports taking clear action so that teachers know they are responsible for their students’ outcomes.

More intense school testing cultures weaken potential benefits of teacher appraisals by increasing the emphasis on test scores in appraisal feedback. This not only leads teachers to see the feedback as less useful but also causes such feedback to lower teacher satisfaction.

In combination, the direct and indirect influences of the school testing culture considerably reduce teachers’ satisfaction. Statistically, the effect can be seen with teachers who work in a school that uses student test scores as part of teacher appraisals and whose principals very often take action to ensure teachers know they are responsible for student outcomes. These teachers report satisfaction levels 0.35 standard deviations lower than those of teachers where student test scores are not incorporated in appraisals and principals never or rarely take action.

Teacher appraisals do not in themselves harm teacher satisfaction. Instead, it is the “pervasiveness of the testing culture, and the overemphasis on student test scores in teacher appraisals that have a profoundly negative effect on teachers and their practice”. School leaders and policymakers must carefully consider how the use of student test scores as an accountability practice shapes the wellbeing of teachers – the people most essential in delivering education.

*

Author Bio:

William C. Smith is a Senior Lecturer in Education and International Development and Academic Lead for the Data for Children Collaborative with UNICEF at the University of Edinburgh. Prior to his position at the University of Edinburgh, he worked as a Senior Policy Analyst at UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report. William’s research focuses on barriers to education for the most marginalized, including how student test scores have shaped educational policy, perspectives, and practice.

*

Photo credit: Avel Chuklanov/Unsplash